Update: For the latest news on the stabilizing brace issue, see my March 21, 2017 update.

Update: For the latest news on the stabilizing brace issue, see my March 21, 2017 update.

…

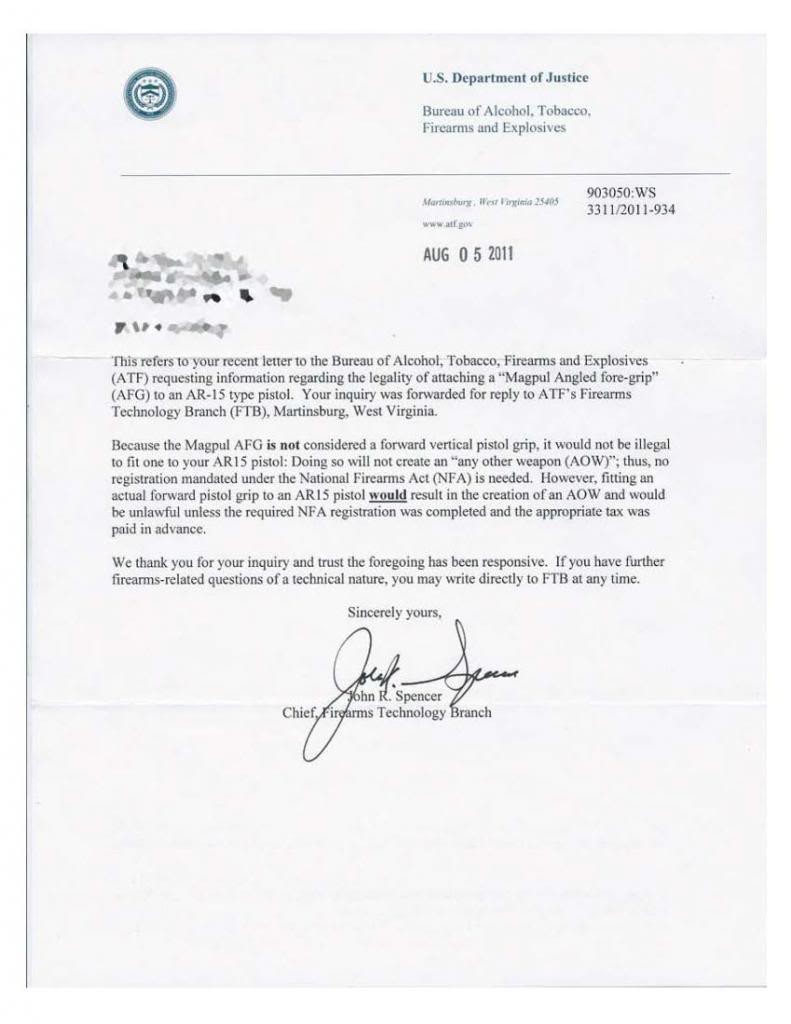

Over the last week I have had a flood of emails from clients wanting to know what I think about the ATF’s seemingly ever-changing position on the Sig brace and other similar products.

For those of you unfamiliar with the issue, let me give you a brief history.

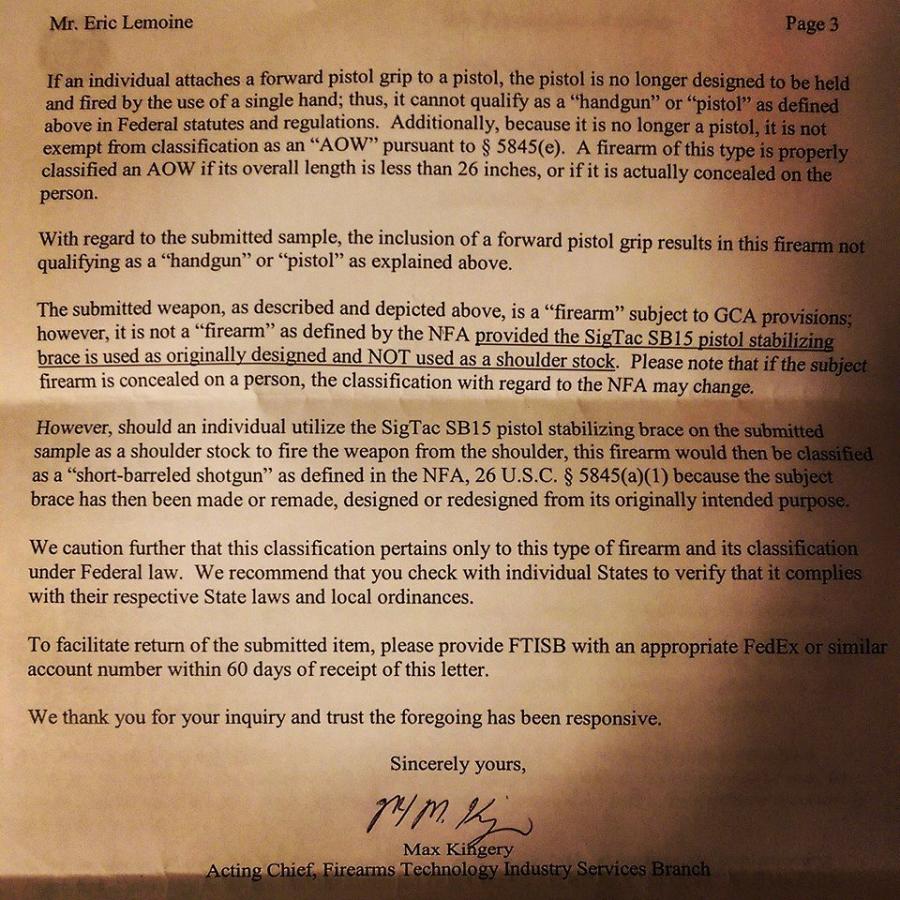

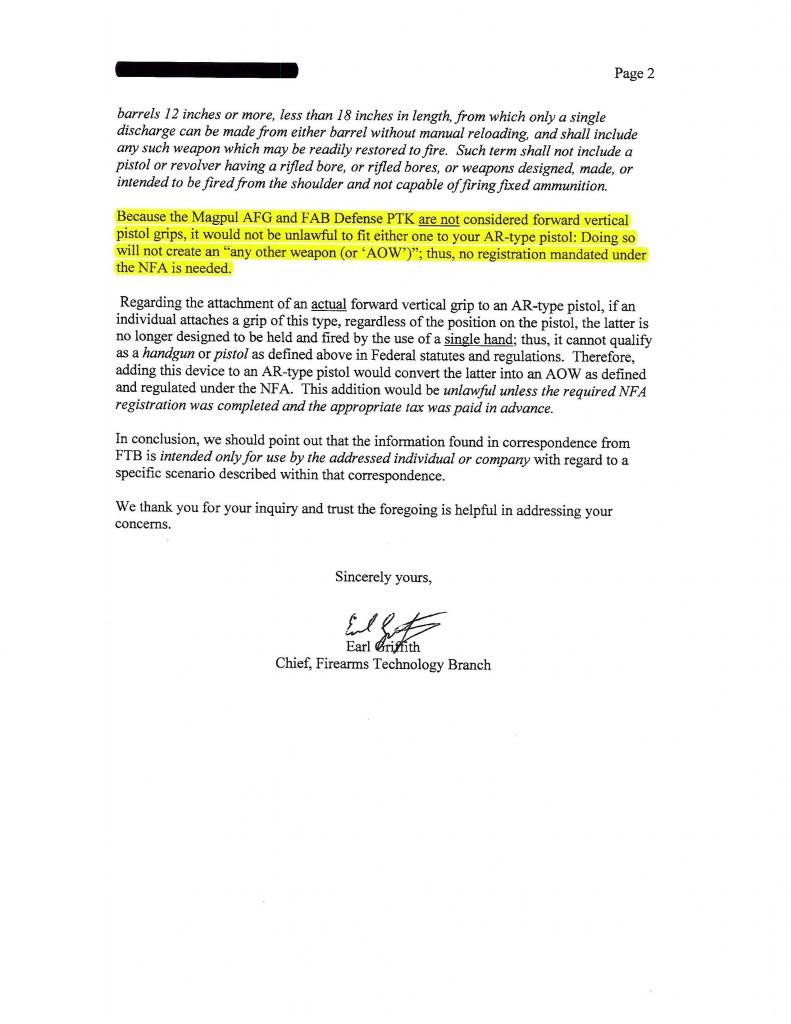

Back in March of this year, a police officer from Colorado wrote to the ATF asking whether firing an AR pistol from the shoulder using a Sig brace as a shoulder pad would cause the pistol to be reclassified as an SBR. The ATF response, shown below, seemed to provide a reasonable response to the question.

The key parts from the letter are:

“[W]e have determined that firing a pistol from the shoulder would not cause the pistol to be reclassified as an SBR … [ATF] classifies weapons based on their physical design characteristics … Generally speaking, we do not classify weapons based on how an individual uses a weapon … Using [the Sig brace] improperly would not change the classification of the weapon per Federal law.”

This seems pretty clear right? And it certainly lead to an explosion in sales for the Sig brace.

But nothing should be taken as a given where the ATF is concerned.

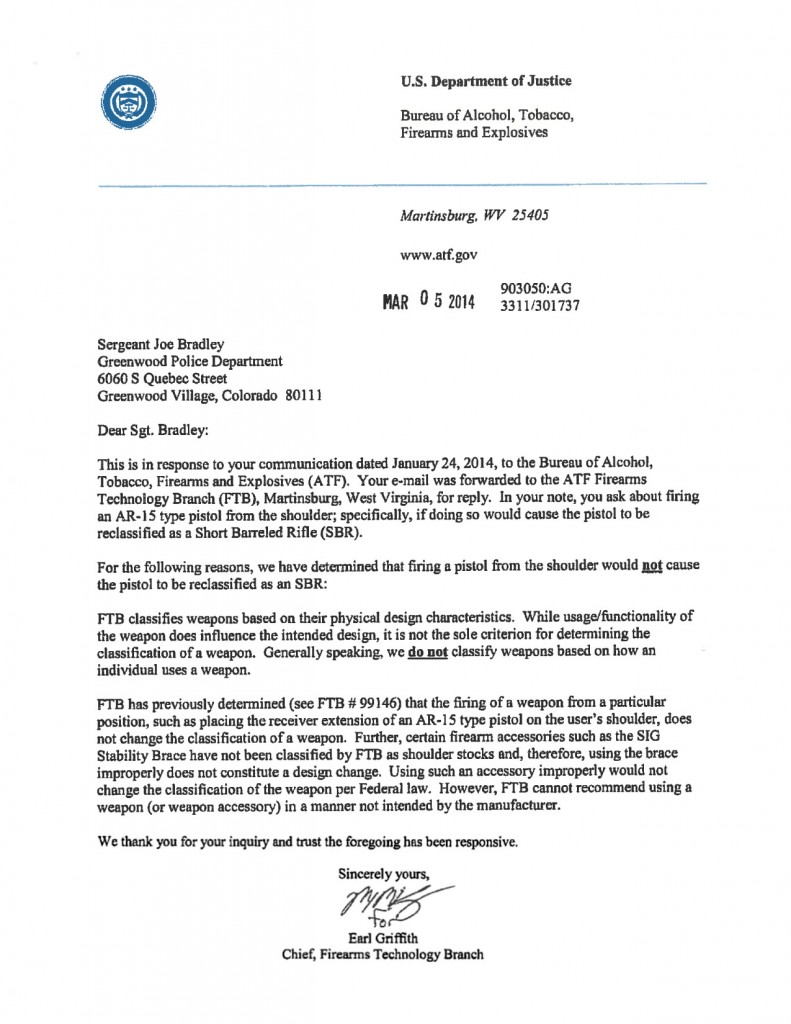

Eight months later … on November 14th, the ATF responded to a request by Black Aces Tactical to classify a shotgun design with an OAL of 27 inches and equipped with a Sig Brace as a firearm not subject to the NFA. In their response, the ATF granted Black Aces’ request based upon the OAL but went on to make several comments seemingly at odds with the earlier letter.

The underlined portion of the letter contains the key difference. It seems to indicate that using the Sig brace in a manner other than that for which it was designed would change the classification of the firearm, after the fact, to a short-barreled shotgun.

But how is that possible? 26 USC 5845(d) categorizes a shotgun as “a weapon designed or redesigned, made or remade, and intended to be fired from the shoulder and designed or redesigned and made or remade to use the energy of the explosive in a fixed shotgun shell to fire through a smooth bore either a number of projectiles (ball shot) or a single projectile for each pull of the trigger, and shall include any such weapon which may be readily restored to fire a fixed shotgun shell.”

If the Black Aces firearm is designed to use the Sig brace, which is NOT considered a shoulder stock, then how can the ATF have the authority to change the categorization since the submitted firearm is not ‘intended to be fired from the shoulder‘?

The answer seems to lie in two other phrases that occur in both 26 USC 5845 and in the ATF letter. Here for the first time we see the phrases “made or remade” and “designed or redesigned” used as part of the logic behind the ATF’s position.

In the Black Aces letter at least, the ATF seems to be implying that using the Sig brace in a manner contrary to the manufacturer’s intentions constitutes a re-manufacturing of the firearm in a different configuration.

But maybe this letter doesn’t really reflect the position of the ATF. After all, following it to its logical conclusion leads to some truly absurd results. As Pennsylvania attorney Adam Kraut noted, under this interpretation, “If an individual attaches the Stabilizer to his AR pistol, goes to the range, shoots it as the manufacturer intended and then hands it to his friend who shoulders it, did it just become an illegal short barreled rifle? Given what FTISB put in their determination letter it would seem that way.”

Have we had any other letters following this same logic? Unfortunately … yes.

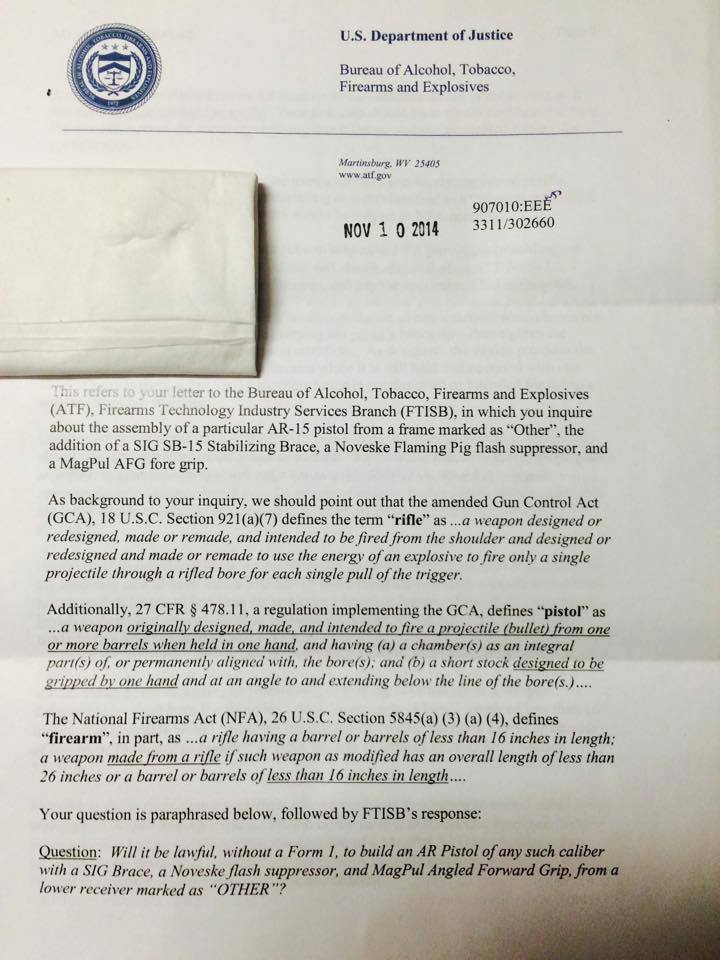

On November 10th, just 4 days before the Black Aces letter, the ATF responded to a letter from an un-named party asking about the making of a pistol configuration with a number of components including a Sig brace. The comments in this letter back up the logic from the Black Aces Tactical letter.

Here again, we see the theme that using the brace as a stock would constitute a ‘redesign’ or ‘remaking’ of a weapon ‘designed to be fired from the should’. Clearly this is a position the current ATF leadership is taking.

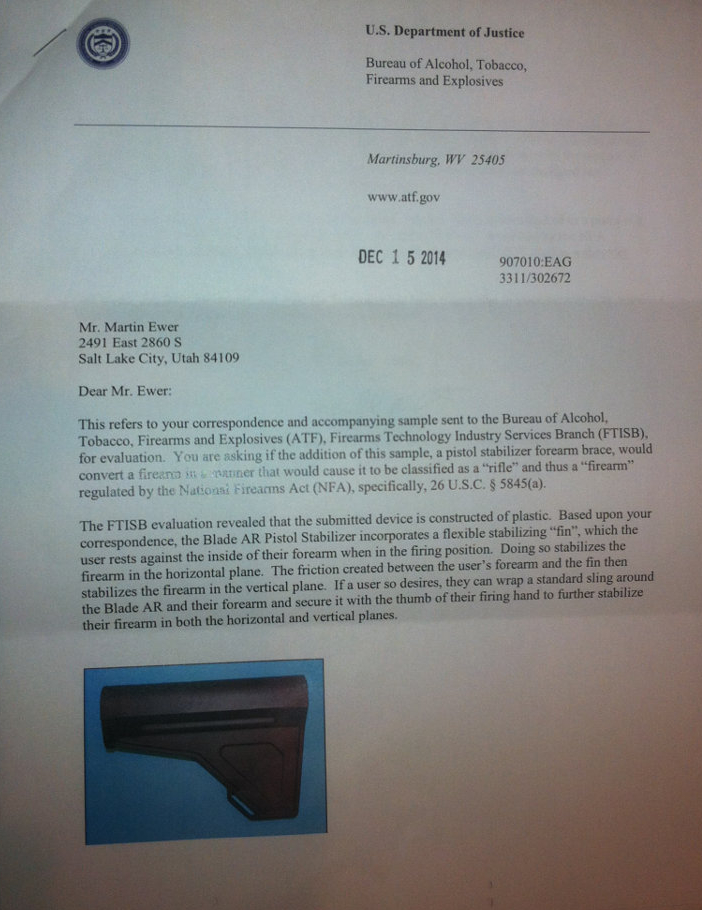

Even more recently, in a December 15th letter, responding to Martin Ewer who has a competing design for a stabilizer brace called ‘The Blade’, the ATF reiterated their position that stabilizing braces are not shoulder stocks but once again goes on to note that this only applies when the braces are used as intended.

While Nick Leghorn over at The Truth About Guns writes that he does not believe the ATF’s position has changed, I am not so sure. His position is that the person writing the November 10th letter “basically outed himself to the ATF [and] tipped his hand, telling them what he really wanted was a short barreled rifle, and was intending to build the firearm for that purpose.”

I do not have access to the original letter, only the ATF response, so I cannot directly comment on this assertion. However, I believe that what we are seeing is deeper than merely a single letter writer not understanding the nuances of law and ‘outing’ their intent to the ATF.

I personally believe that the ATF is adopting an interpretation that using a stabilizing brace in a manner contrary to the manufacturer’s intentions constitutes a re-manufacturing of the firearm in a different configuration. And while this interpretation leads to some absurd results, I fear we may see an attempt to prosecute a gun owner under this interpretation before it is over.

Only time will tell.

Today one of my clients received an email with an approved eForm 1 attached. He immediately forwarded it to me so that I could update the schedule of assets in his

Today one of my clients received an email with an approved eForm 1 attached. He immediately forwarded it to me so that I could update the schedule of assets in his

There seems to be some disagreement in the legal community here in Virginia as to whether or not the decision in

There seems to be some disagreement in the legal community here in Virginia as to whether or not the decision in