I was recently debating with a gun control advocate about the increased burden that is imposed on law-abiding gun owners when we add more and more records to the NICS system. I was specifically discussing the prevalence of erroneous matches.

Her response to this was to dismiss it out of hand as not a problem since “there is an appeal process that they can use to correct those mistakes.”

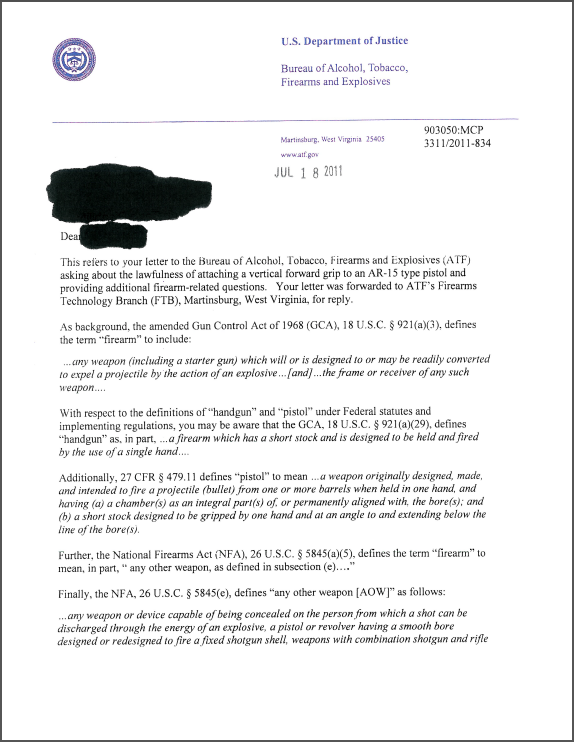

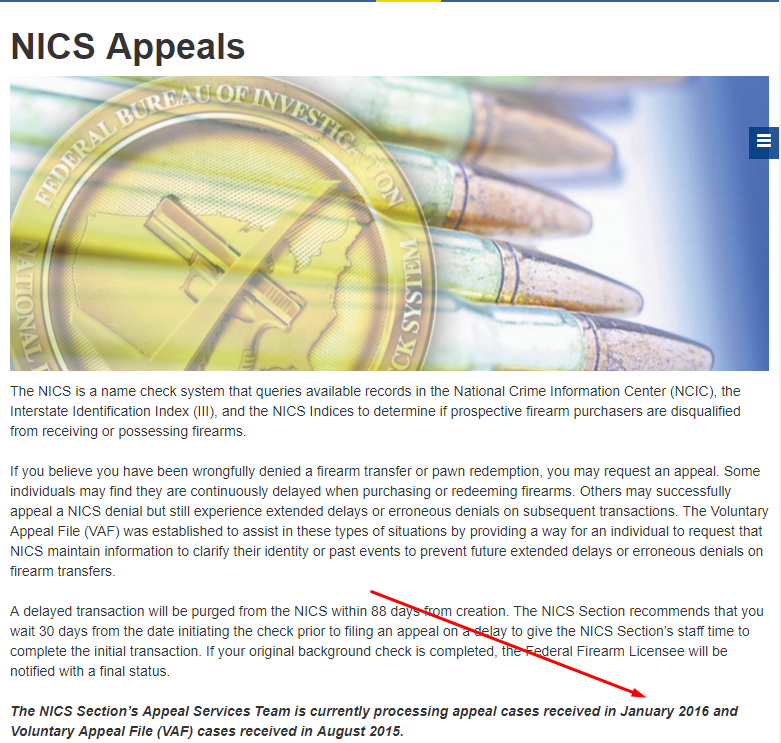

If you are familiar with the NICS appeal process and its recent history, you will understand why I groaned at that statement. As of today (May 4, 2018), the following screenshot shows where the FBI is in processing their backlog of NICS appeals.

Let me do the math for you. They are processing appeals received two years and four month ago! This is due in large part to the fact that the FBI, during the Obama Administration, completely stopped processing NICS appeals.

To her credit, the gun control advocate admitted that this is not satisfactory due process and expressed shock at this state of affairs.

That brings us to the Fix NICS Bill which was passed as part of the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2018. This bill amends the ‘Correction of erroneous system information’ provision of the Brady Handgun Violence Prevention Act, codified at 34 U.S. Code § 40901(g) by adding the following at the end:

For purposes of the preceding sentence, not later than 60 days after the date on which the Attorney General receives such information, the Attorney General shall determine whether or not the prospective transferee is the subject of an erroneous record and remove any records that are determined to be erroneous. In addition to any funds made available under subsection (k), the Attorney General may use such sums as are necessary and otherwise available for the salaries and expenses of the Federal Bureau of Investigation to comply with this subsection.

This seemingly imposes a hard limit of 60 days to reply to NICS appeals. However, I am less than hopeful. There are two reasons for my scepticism:

- There are no penalties or requirements imposed on the 61’st day. Without that, the deadline has little meaning. This is backed up by reason number 2.

- The text of the existing law (which is two years and 4 months behind) already requires that corrections be made ‘immediately’:

The prospective transferee may submit to the Attorney General information to correct, clarify, or supplement records of the system with respect to the prospective transferee. After receipt of such information, the Attorney General shall immediately consider the information, investigate the matter further, and correct all erroneous Federal records relating to the prospective transferee and give notice of the error to any Federal department or agency or any State that was the source of such erroneous records.

There does appear to be funding for increased staffing in the Fix NICS bill which might provide an incentive to reduce the backlog and live up to the new requirement. We will have to watch their progress over the next few months to see if that is the case.