Whenever you need to temporarily or permanently transport a Short-Barreled Rifle (SBR), Short-Barreled Shotgun (SBS), Machinegun, or Destructive Device (DD) across state lines, you will need an approved ATF Form 5320.20 (more commonly known as just Form 20) before doing so.

Because we often do not have the time to resubmit a Form 20 before a shooting competition or move, it is important that you do not fall victim to some of the more common errors that can occur with this form (especially when the items are owned by a trust).

Mistake 1) Putting the wrong name for the registered owner

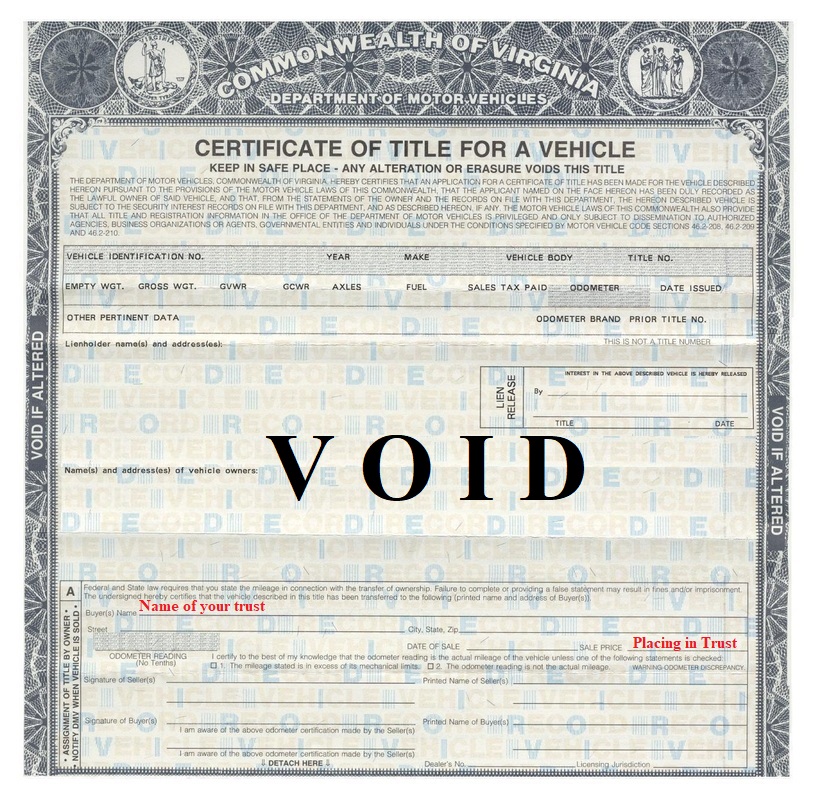

In box 1 of the Form 20 it asks for the name and address of the registered owner. If your NFA items are owned by a trust then this should contain the name of the trust and not your name. If this is wrong the Form 20 will be denied.

Solution: We are going to learn a single rule that will solve almost every problem with the Form 20. “It should match the corresponding field on the approved Form 1 or Form 4 for the item in question.”

Mistake 2) Mistyping the Manufacturer, Model, Caliber, Serial #, OAL, Etc.

The ATF matches these Form 20’s to the National Firearms Registration and Transfer Record (NFRTR). Therefore, if you do not provide them the information as it was entered your Form 20 will be denied.

Solution: The information for each item should match the corresponding field on the approved Form 1 or Form 4 exactly (and this is true even if you have subsequently come to believe that the approved Form 1 or Form 4 is incorrect, at least until such time as the information is corrected in the NFRTR).

Mistake 3) Leaving a required field blank

Other than the fields listed above, there are fairly few required fields. Make sure to answer the remaining fields as follows:

- For temporary transportation, Box 3 From and To Dates must be filled in and should not exceed 365 days in length.

- For permanent transportation, Box 3 From and To Dates must be filled in and should contain projected start and end dates for transporting the items.

- For temporary transportation, Box 5 should contain: “Target practice, sporting events, and all lawful purposes” .

- For permanent transportation, Box 5 should contain: “Permanent change of address”.

- Boxes 6 and 7 must be filled in for both temporary and permanent transport.

- Box 8 should contain something similar to one of the following (depending on circumstances): “Personal conveyance”, “Common Carrier”, or “Air Carrier”